How is mindful awareness of now different from being stuck in a NOW Bubble?By Hanna Bogen, M.S., CCC-SLP and Carrie Lindemuth, M.Ed./ET “There are only two ways to time travel (that we know of): to look at the stars and to think with the front of your brain.” I heard this from a friend years ago while on a camping trip that offered some of the best stargazing I’d ever done. Although she was actually referencing a conversation about delayed light coming from the stars, this statement was the start of a deep fascination with the human brain’s ability to shift between awareness of the past, present and future. This phenomenon, known as mental time travel, encompasses our unique ability to use past experience, and future interest, to impact our decisions about present action. Mental time travel heavily involves the frontal lobe of the brain, especially the prefrontal cortex, and is at the crux of successful self-regulation. One’s ability to self-regulate is ultimately judged by how they act in the present moment. The integration of mental time travel into responding is dependent upon how well someone can expand his/her NOW Bubble long enough to self-assess his/her current state, past experiences, and future interests before acting.

Understanding the NOW Bubble In Brain Talk, the NOW Bubble is the immediate moment following a trigger or stimulus. In this moment, impulses are activated in order to drive action that seems most in line with the brain’s seek and/or avoid urges. For example, if someone cuts you off on the freeway, you may feel the impulse to yell out your car window in the NOW Bubble. For some, that impulse takes over and drives a reaction; they find themselves moving faster than the speed of thought. In this case, action is driven only by what would feel good right now; past experience and future interest are not considered. Understanding mindful awareness of now According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, mindfulness is open hearted, moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness of now (i.e., the present moment). Mindful awareness of now involves observational, curious examination of present emotions, sensations, and thoughts. For example, mindful awareness of now following news about a promotion at work might involve nonjudgmental identification of your emotional state (e.g., elated, proud, excited), sensations (e.g., warm, energetic, heart racing), thoughts (e.g., “This is going to be such a great opportunity!”), and impulses (e.g., desire to celebrate, wanting to share news with friends). How do the now’s compare? Being stuck in your rigid NOW Bubble makes you a hostage to your present impulses rather than an empowered participant in the present experience. One of the goals of mindfulness is to “insert the pause” between stimulus and response to allow for choice in how to respond rather than feeling “along for the ride” with your reaction. When practicing mindful awareness, you remain in control of your engagement with the now as opposed to the now is controlling you. The more effectively you can mindfully observe the now, the more you can expand your NOW Bubble to incorporate past experience and future goals. In other words, you are less likely to react faster than the speed of thought. Often, one’s awareness of their present experience is rooted in his/her emotion(s) in the moment. Emotions are like the weather: you can’t control whether you have calm, gentle emotions or strong, stormy emotions. You can, however, control how you respond to your emotions. This is the core of emotional-regulation. Although you can’t control the forecast (emotional or weather forecast), you can engage mental time travel to sometimes predict your emotional experiences based on your past memories of a triggering situation. Acknowledging that similar triggers create similar emotional climates allows individuals, especially those with strong capacities for mental time travel, to anticipate how they might feel going into a situation. This creates a platform to proactively plan, practice, and master emotional coping strategies to help make uncomfortable situations a bit more comfortable. Without awareness of your emotional state, your reactions are driven by the intensity of the feelings. In a highly triggering situation, the limbic (i.e., emotional, survival) brain shuts down communication with cortical thinking areas of the brain. This occurs as part of the brain’s survival mechanism to avoid danger and seek opportunities. Staying alive in a threatening situation is more important than engaging in critical thinking. The problem with this survival safeguard is that not all situations that trigger a fear response are life threatening. Tests, public speaking, arguments with friends, schedule changes…while emotionally triggering, none of these lead to eminent demise. Obtaining potentially awesome opportunities before they disappear is critical for survival if you have limited access to resources. The problem with this survival safeguard is that not all opportunities that trigger your pleasure-and-reward circuit in the moment align with your ultimate goals in the future. In triggering situations like these, cortical shutdown prevents the brain from engaging in mental time travel to consider the past and future in order to manage the present. Mindful awareness of now allows you to be in a dynamic, aware, open, flexible cognitive “headspace.” The cortical thinking brain remains online, meaning you are able to access present awareness (i.e., “What do I notice right now?”), past experience (i.e., “What do I know from the past?”), and future thinking (i.e., goal identification, anticipating consequences, awareness of emotional and/or physical motivation), in order to choose: do I follow my impulse and react, or do I consider my options and respond?

0 Comments

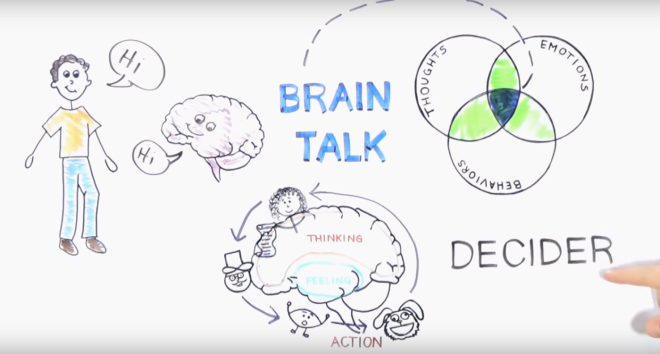

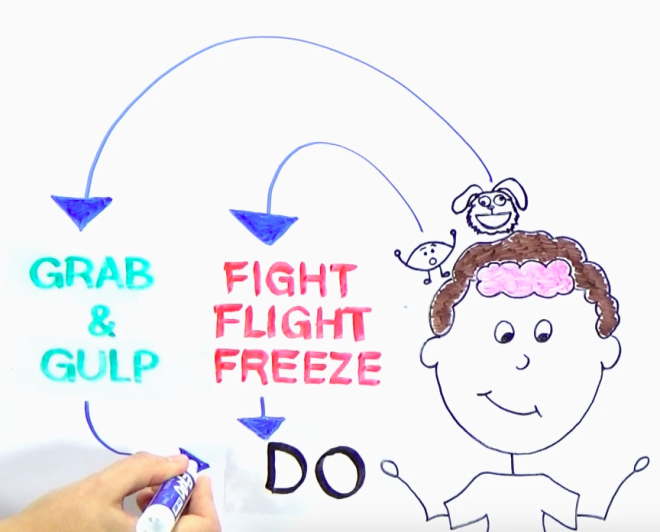

By Hanna Bogen, M.S., CCC-SLP As adults, we spend an extraordinary amount of time thinking we've got our students' and children's problems figured out: "I know why he's mad...it's because he can't get the Legos to fit together!" "She must be sulking because her friends left her out during recess today" Grown ups certainly have more life experience than kids, and sometimes we are great at reading between the lines to sense what might be going on under the surface of a seemingly shallow problem. That being said, I'm always amazed at how often I (and others) forget to do the most logical first step in problem-solving with children: asking them what's wrong. I'm not talking about a "grazing" question; the kind you ask when you already have an answer in mind and are merely extending a formality. I'm talking about a thoughtful, considerate, invitation into problem-solving and self-regulating dialogue; the type of invitation that comes along with Ross Greene's initial steps of Collaborative Problem Solving (for more information about Collaborative Problem Solving, visit: http://www.livesinthebalance.org). Here's the tricky thing about asking a child to describe an underlying trigger for dysregulation: more often than not they don't yet have the awareness and skills to effectively communicate it. The way I see it (stemming from my research brain rather than my opinion brain), you need the following, in this order, to effectively express a trigger for dysregulation: 1. Metacognition: the ability to think about your own thinking and emotional state well enough to figure out what's going on internally. This is where brain learning and mindfulness-based strategies come in! 2. Self-regulation: regulation of your thoughts/attention, emotional responses, actions, and motivation in order to behave in an expected way for a given situation. Self-regulation and executive functioning are inherently tied, since self-regulation sandwiches executive function thinking skills (i.e., using mental schemas to manage complex tasks) by allowing for inhibition of impulses and the ability to follow through with the plan. 3. Strong (or at least functional) verbal and nonverbal communication skills: collective expressive communication skills to allow you to get your ideas from your "thought bubble" into someone else's "mind movie." I know I'm a speech-language pathologist, and therefore would typically hone in on the third step of this structure. But I'm a unique breed of SLP when it comes to my areas specialization, and I actually live far more in the domains of steps one and two. In my adventures (and misadventures) of working in the world of self-regulation and executive functioning (ok, ok, they're essentially one in the same), I've become very clear that kids need to understand their brains. More generally, everyone should have a basic understanding of their brains that goes beyond "It has a left side and a right side." As therapists (and teachers, and administrators, and psychologists-hi everyone!), we are, at the core, brain specialists. If we want kids to get to step three (effective communication of their triggers), we need to start by TEACHING them metacognition and self-regulation. This matters so much to me and my fabulously brilliant colleague, Carrie Lindemuth, M.Ed/ET, that we created a curriculum designed to teach students about key concepts and functions of the brain: Brain Talk. This narrative-based curriculum consists of eight short, white-board animated videos and corresponding lessons plans, discussion points, worksheets, and activities. Different lesson plans and activities exist for early elementary, upper elementary, middle/high school, and a therapy model. Through these videos and the corresponding learning activities, students are introduced to their amygdala (Myg), basal pleasure-and-reward system (Buster), hippocampus (Ms. Hipp) and prefrontal cortex (The Professor), and what happens in the brain during a "Myg Moment" (i.e., fight/flight/freeze avoiding reaction) or "Buster Bam" (i.e., dopamine-driven grab-and-gulp reaction). Additionally, they learn how the integrated conversation (i.e., Brain Talk) between their "emotional" limbic brain and their "thinking" cortex leads to strategic thinking and self-regulated decisions. Many of us don't have the opportunity to learn about our brains until we are in the midst of a crisis, whether it be anxiety, depression, hyper-impulsivity, or significant dysregulation. What a gift we could give to our students to teach them these critical metacognitive skills from the get-go! The Brain Talk curriculum is available through an annual subscription ($50.00/year) at the Brain Talk website (www.braintalktherapy.com). An annual subscription to the curriculum provides access to the full curriculum suite, as well as new materials as they are added throughout the year.

|

ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed